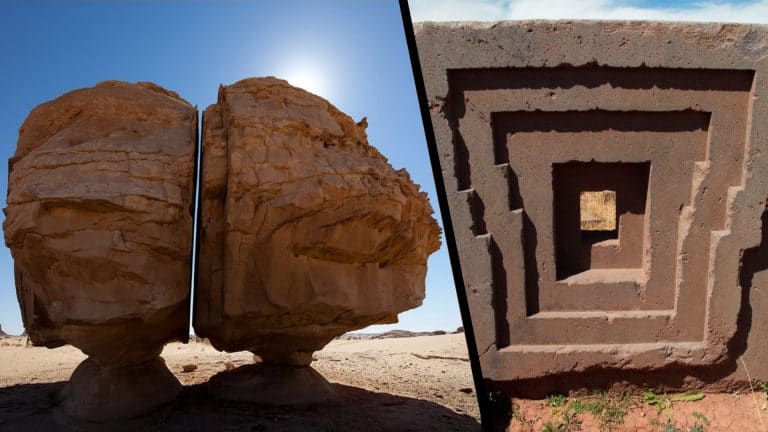

High in the Andes Mountains, over 12,000 feet above sea level, near the shores of Lake Titicaca, lay the ancient pre-Inca ruins of Puma Punku – “Door of the Puma.” These ruins, some 45 miles west of the modern city of La Paz, Bolivia, stand as one of earth’s greatest mysteries.

By the time it was discovered by the Incas, Puma Punku was already abandoned; there exists no record beyond that of who might have built it, or when. Traditionally, archaeologists dated Puma Punku to somewhere around 500 CE. But in the 1920s, an Austrian archaeologist and explorer named Arthur Posnansky, who had spent decades at the site, proposed something quite different. He noted that on the first day of spring, the sun rose directly above the center of the ruins, through a stone archway. It seemed, Posnansky surmised as he examined the layout, that as the sunrise moved along the horizon as the days of the year passed, it would rise over the two cornerstones on either side of the archway on the summer and winter solstices. Yet, when those days came, it did not. This puzzled and disappointed Posnansky, until, after further research, he realized that the sun would have raised exactly over those spots approximately 17,000 years ago. Thus, Posnansky asserted that Puma Punku was built by some sort of prehistoric civilization lost to the history books, that the site was more than ten times as old as archaeology had previously hypothesized.

And yet, who built Puma Punku, and whether they existed 1500 years ago, or more than 15,000, is not even the greatest mystery of the site. It is not so much about who built it, but how they did so.

Unexplained Ancient Stone Cutting Technology

The structures of Puma Punku are built of huge stones, granite, and diorite, a series of blocks that fit together like a puzzle without mortar holding them in place, positioned so perfectly that a razor blade can’t fit between. Even more incredibly, the structures have smooth, flawless right angles, made of perfectly straight stones with circular holes drilled in them at exactly the same size and depth. Modern experts have asserted that even with modern technology, Puma Punku would be near impossible to replicate. So how could it possibly have been constructed by an ancient civilization?

For answers, first travel across the world to Egypt and the infamous unfinished obelisk at Aswan. To this day, the enormous obelisk lays encased in granite bedrock, a monstrosity some 42 meters long and well over 1000 tons, more than twice the size of the largest completed Egyptian obelisk.

But it was not just the size that confused modern archaeologists. More perplexing, the obelisk was carved out of pink granite, an extremely hard rock, and one much harder than the tools used by ancient Egyptians. Simply, if Egyptians had used their bronze and dolerite tools on pink granite, the tools would have worn out faster than the rock. Further, the obelisk was lying in a deep trench, which would not have left room for a hard blow. If an Egyptian hammer already weren’t strong enough to carve the granite, it would be even less so without room to wind up and strike firmly.

With this in mind, archaeologists examining the obelisk noticed what appeared to be strange tool marks on the side, described as “scoops,” as if done with a belt sander on wood. This was not a pattern made by hammering tools, nor, for that matter, any tool the ancient Egyptians possessed. Manufacturing expert Chris Dunn, who examined the site, reached a suggestive conclusion:

‘The unfinished obelisk offers compelling indirect evidence regarding the level of technology its creators had reached – not so much by indicating clearly what methods were used, but by the overpowering indications of what methods could not have been used.’

And yet, the obelisk at Aswan is not the only Egyptian evidence of such a thing. Consider the massive granite boxes found at the Serapeum at Saqqara, a site near Memphis in lower Egypt. These boxes were finished to unbelievably high accuracy, with sharper dimensions than should have been possible at the time, mainly when using granite. In modern times, masons use diamond-tipped, hydraulic pressured machines loaded with ample cooling fluid to cut granite, a far cry from the primitive tools of ancient Egypt.

Or, what about the many examples of Egyptian stonecraft pottery carved out of granite and other hard rock with incredible precision? Experts assert that even with modern technology, this stonecraft pottery cannot be replicated. If not so-called ‘modern’ technology, just what sort of technology did the ancient Egyptians possess then? Chris Dunn offers a dramatic explanation:

“I believe that these artifacts that I have measured in Egypt are the smoking gun that proves, without a shadow of a doubt, that a higher civilization than what we have been taught existed in ancient Egypt. The evidence is cut into the stone.”

The question then becomes, if this is, in fact, ‘ evidence’ of a ‘smoking gun,’ what does this evidence show? What is the smoking gun? That is to say, how did they do it?

Microscopic Research on Ancient Stone Work

In the 1980s, a group of researchers from St. Cloud University in Minnesota led by the enigmatic archaeologist Ivan Watkins endeavored to study the stonework of the incredible Inca ruins of Machu Picchu in Peru, at an up-close, microscopic level. Hard rock, such as that which makes up Machu Picchu’s mighty structures, contains a mix of numerous minerals with varying degrees of hardness, which can be seen when examined under a microscope. When force is applied to the rock, such as by hammering or grinding or sanding, the weaker minerals crack and break, while the harder ones stay together. By studying the stonework of Machu Picchu microscopically, Watkins and his team hoped to find out more about how the rock was cut, and thus how the structures were made.

And yet, upon examination, Watkins and his team were stunned. The surface of the rock was not an uneven mishmash of broken and held together minerals, but rather, a smooth, slick surface, almost as though the rock had been exposed to extreme heat, melting quartz fragments into a sort of glaze which filled in the stone’s microscopic irregularities.

The research was taken up by a different team, led by a geologist from the United States Bureau of Mines named David Lindroth, who sought to discover how the stone blocks of Machu Picchu had been cut so as to give the rock a glazed effect. After some effort, Lindroth and his team found that by focusing a laser with 100 watts of power at a 2-millimeter area and moving it back and forth, a stone could be cut by the beam. This was a process they called “thermal disaggregation.” Regardless of what it was called, though, it seemed that Lindroth and his team were suggesting that the Incas could have cut the stones used to create Machu Picchu with lasers.

And speaking of ancient laser cutting technology, we must mention the mysterious Al Naslaa rock found in the Tayma oasis in Saudi Arabia. This massive block is split through the center by a very precise and clean-cut, almost as if the rock was sliced with some kind of laser technology. Apparently, the Incas were not the only ones who possessed this kind of technology.

It is interesting to note that, like the Egyptians and the ancient peoples of Lake Titicaca, the Incas worshiped a sun god. They had a yearly festival called the ‘Festival of the Sun,’ during which a priest would use a bracelet with a concave gold charm to reflect the sun and light a pile of cotton on fire. Some have suggested that this is a clue.

Solar Powered Laser Cutting Technology

Some have gone further. Like Ivan Watkins, who, in a 1986 article published in the LA Times, proclaimed, “The Incas used solar power, not manpower, to cut the huge stones they used to build their massive cities.” According to Watkins, the Incas would use large parabolic dish-shaped reflectors made of gold, the size of two men across, to focus the sun’s energy into a beam of light that could cut rock. “There’s no doubt in my mind that they knew how to do it,” Watkins asserted.

The existence of large gold disks at Inca temples is confirmed by the records of Spanish conquistadors, who historians suggest likely cut up the gold disks for poker chips before melting them down and sending them back to Spain. If these disks were used as Watkins suggests, one might laugh at the stereotypical actions of conquerors – taking the loot but missing the point.

But what then, is the point? Is it possible that the Incas, and other ancient civilizations like the Egyptians and those who built Puma Punku, had knowledge of how to harness the power of the sun? All three of these civilizations accomplished seemingly impossible feats of stonework, all three lived in places with yearlong sun and worshiped a sun god. Could all three have possessed a knowledge of some sort of ancient solar laser?

Perhaps. Or perhaps there is even more to it than that.

Ancient Egyptian Stone Cutting Device

A number of years ago, a strange story started making its way around the fringes of the archaeological community, on early internet message boards and in hushed tones in the backrooms of iconoclast academia.

Apparently, a young American archaeologist in Egypt had taken it upon herself to do some, to put it mildly, snooping around. This was probably not an unusual fantasy for archaeologists regularly stymied by the notoriously secretive Egyptian government. In this case, the young American picked the lock of a nondescript Egyptian storeroom at the end of some dusty hallway and opened the door to a small room stacked to the brim with hundreds of tuning forks, some small, 8 or 9 inches in size, some as big as 8 or 9 feet, each like the letter’ U’ at the end of a long handle, resembling a pitchfork. Most curiously, each fork had a taut wire stretched between the prongs of the ‘U.’ When the wire was plucked, the fork would vibrate.

Note that, officially, the tuning fork was not invented until 1711 by a British musician named John Shore. So what were these tuning forks doing at an Egyptian archaeological site? And if these forks had been found there, would this not be something to share with the world, at least in as much as it seems to predate the recorded invention of the tuning fork?

More importantly, what could these forks, and not one or two, but hundreds, have been used for, some small, as if made for finer details, others large, as if made for heavy work? Consider that ancient Egyptian art often portrayed deities with a rod in their hand, specifically a staff with a forked base in the shape of a ‘U,’ and a pronged head, usually made out to look like some sort of animal. This is not any staff, but what is known as the Was-scepter. In ancient Egyptian beliefs, it represented power. But what sort of power? Maybe this is more literal than it seems.

Remember the solar laser spoken about by Watkins, accomplished by focusing the electromagnetic waves of the sun. Some have asked, why do the waves have to be electromagnetic? Why not waves of sound?

This idea is not as far fetched as it may initially seem. In fact, as far back as 2000, NASA had begun work on what they called an “Ultrasonic/Sonic Driller/Corer,” more simply, a device that uses sound waves to hammer through materials. This is a device NASA envisions as being used to explore beneath the surface of other planets in the future.

More recently, scientists from the University of Michigan discovered a way to concentrate sound waves at a frequency 10,000 times higher than humans can hear, into a “beam“, which then acts as an “invisible knife.” In other words, scientists at the University of Michigan have created an invisible laser beam of sound.

This so-called ‘sonic drilling’ relates directly to the civilizations of ancient Egypt and elsewhere. By sending sound vibrations through the handle of a tuning fork, say, by plucking a taut wire strung between the prongs of the ‘U,’ the bottom end of the fork can be turned into a “high-frequency jackhammer,” one which, even if it was made out of copper, would be able to cut granite with precision.

Perhaps this is how the Egyptians cut rock that was too hard for their tools. And if the same characteristics found in Egyptian stonework were found elsewhere in the world, at places like Machu Picchu and Puma Punku, perhaps each of these ancient civilizations possessed since-forgotten secrets of the power of sound.

Or, perhaps the secrets go even deeper. Perhaps the power of sound was something the ancients knew all too well, better, in fact, than we know in modern times.