The Giza Plateau in Egypt is one of the world’s most well-known historic sites, recognizable at a glance to most people on earth. But what if the enduring image of the Giza Plateau we know today, its legendary Sphinx gazing out from beneath its three mighty pyramids, is wrong?

According to some historical records, our modern conception of Giza is incomplete, missing crucial features present at the time of the ancient Egyptians.

Could our modern understanding of the Giza Plateau, and ancient Egypt as a whole, really be mistaken? If features are missing, where did they go? And what other mysteries of the Giza Plateau might be waiting to be uncovered?

Frederic Norden's Accounts of the Fourth Pyramid

Frederic Louis Norden was born in 1708 in southern Denmark, the fourth of five sons of an artillery captain in the Danish military. At only 14 years old, Norden entered the Danish Naval Academy, where he quickly proved to be something of a prodigy.

He had an innate gift for drawing and cartography, a talent so great that it caught the attention of the Danish King himself. In short order, Norden was sent abroad by the king to utilize his unique skills in the Netherlands through a study of military installations. His drawings proved so valuable that he was instructed to continue to France and Italy.

By 1737, Norden’s work was so well-respected that he was personally chosen by the king for a very special mission. He was to join an expedition down through Egypt to the mysterious kingdoms of Ethiopia and Sudan, serving as the king’s official representative and attempting to forge economic ties.

The expedition reached Egypt in June of 1737, but as it traveled south, it quickly fell upon bad luck, problems with weather, problems with their ship, which prevented the party from traveling further. Yet, the expedition’s bad luck turned out to be Norden’s good fortune, the stroke of fate that completed his evolution from prodigy to legend.

Stuck in Egypt and with little else to do, Norden had the opportunity to construct a comprehensive record of everything he saw, the people, architecture, and monuments around him, along with detailed hand-drawn maps. Few Europeans had ever seen Egypt like Norden had, and fewer still had recorded their experience.

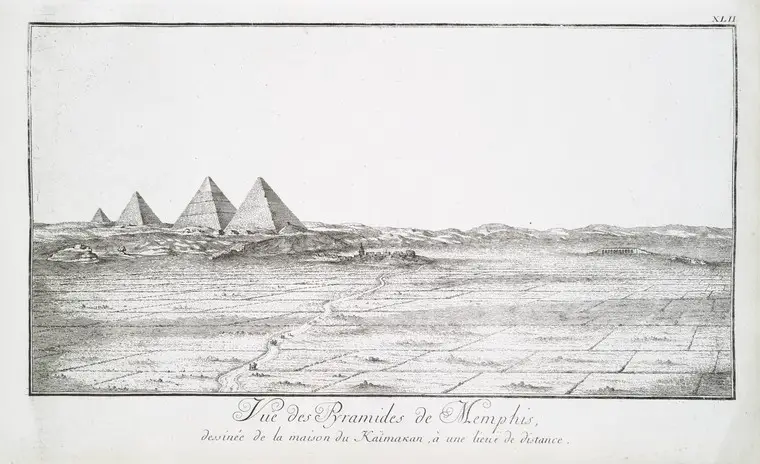

Upon his return to Europe in 1738, this incredible record was published in what became Norden’s seminal work, Voyage d’Egypte et de Nubie, while Norden himself was elected as a member of the prestigious Royal Society of London.

To this day, one particular aspect of Norden’s Voyage stands out – the way in which he described Egypt’s Giza Plateau. In his words,

“The principal pyramids are at the east, south-east of Giza … There are four of them; they deserve the greatest attention of the curious; although, we see seven or eight others in the neighborhood, they are nothing in comparison to the former.

The two most northerly pyramids are the greatest and have five hundred feet perpendicular height. The two others are much less, but have some particularities, which occasion their being examined and admired.”

Norden directs much of this examination and admiration to the fourth pyramid, which he describes in detail.

“The fourth pyramid is a hundred feet lower than the third. It is without coating, closed, and resembles the others, but has no temple like the first. It has, however, one particular feature that deserves attention; which is, that its summit is terminated by a single great stone, which seems to have served as a pedestal …

The fourth pyramid has been made, upwards above the middle, of a stone blacker than the common granite and harder to work with. It is, moreover, situated out of the line of the others, being more to the west … it makes a series with the three others.”

Wait, four great pyramids? What was he talking about? How could Norden, with his prodigious and internationally recognized talent, have documented four pyramids, when everyone familiar with the Giza Plateau in modern times knows that there are three?

Some modern skeptics of Norden’s work have provided an answer. They assert that he must simply have confused one of Giza’s smaller satellite pyramids for a fourth great pyramid. Despite his reputation for incredible precision, skeptics believe Norden simply made a mistake.

Except, in Norden’s account, he specifically describes “seven or eight” smaller satellite pyramids as distinctive and supplementary, “nothing in comparison” to the four great pyramids. Further, he describes the fourth pyramid as constructed “from a stone blacker than the common granite and harder to work with,” while the satellite pyramids of the Giza Plateau were constructed of sandstone.

Norden was not unaware of the satellite pyramids, he did not appear confused, rather he actively documented the satellite pyramids as different from the main four he recorded. To suggest Norden simply mistook a satellite pyramid for a fourth great pyramid seems lazy at best, disingenuous at worst.

But regardless of the veracity of Norden’s account, there is something else, something which modern skeptics seem to ignore – evidence of a fourth pyramid on the Giza Plateau goes beyond just the work of Frederic Louis Norden …

De Bruijn's Accounts of the Fourth Pyramid

Prior to the 18th century, what most European nations knew about Egypt was mostly made up of a hodgepodge combination of biblical accounts, ancient records, and the imagination of historians. Egypt was little more than a fantasy; it had yet to be depicted by someone who had actually been there themselves.

This is why early European depictions of Egypt showed things like the biblical Noah in a flood scene with a large pyramid as the backdrop, or the biblical Joseph standing before the pyramids with bales of wheat.

But that all started to change at the end of the 17th century …

It perhaps began in 1674, when the Dutch artist and famed traveler Cornelius de Bruijn set off on the first of two legendary tours he would take in his life. For almost 20 years, he traveled through the territories of western Asia and northeast Africa, recording in detail his observations on the people, plants, animals, and architecture he came across.

In 1698, having returned to Europe, de Bruijn published an incredible illustrated book on his journey, Travels in the Principal Parts of Asia Minor. The book, regarded as one of “the most beautiful travel accounts of all time,” was an immediate hit, providing Europeans with first-hand information that was far better than anything known at the time.

Within the book, one section stood out for its unheard-of detail – the portion covering de Bruijn’s travels through Egypt.

While he was not the first European of his time to have visited Egypt, the few who’d come before him had merely been passing through on their way to the Holy Land and Jerusalem. De Bruijn was the first to stop and spend time there, and record in detail what he saw. He was the first to depict the Grand Gallery and the interior of the pyramids, the first to give an accurate description of the Sphinx.

It should be no surprise that to this day de Bruijn’s work remains relevant and sought after. Yet, to revisit this work today, one might be struck by something most curious.

Look at de Bruijn’s depiction of the Giza Plateau.

That’s right … like Frederic Louis Norden, Cornelius de Bruijn showed the Giza Plateau with four great pyramids, not three. Could both of these celebrated illustrators and historians really have each have made such a glaring error on something as straightforward as counting the number of pyramids on the Giza Plateau?

Maybe there was no error.

Maybe confirmation of this has been hiding in plain sight all along …

The Wall of the Crow

Only a few hundred yards to the south of the Sphinx lies an enormous ancient wall constructed of giant limestone blocks weighing many tons each. Standing at over 650 feet long, 30 feet high, and 30 feet thick, it is known as the Wall of the Crow.

Despite its magnitude, the Wall of the Crow is not usually part of the popular conception of the Giza Plateau, not a tourist hot spot, not depicted on postcards.

But why not?

One answer might be that modern archaeologists are baffled by the wall; they cannot figure out what it’s doing there. Some have suggested it could have been built to protect the Giza Plateau from the floodwaters of the ancient Nile River, while others have proposed it was the boundary wall of an ancient city. But neither of these theories have explained why the wall does not then extend past the end of the pyramid gallery complex. If it were a wall in this sense, surely it would encompass the entire settlement.

Some have a different explanation.

Consider that all three of the Giza Plateau’s main pyramids have their own causeway leading to where the Nile River once extended. The eastern end of the Wall of the Crow extends to where the Nile would have been, leading some to suggest it is not a wall at all, but a fourth causeway.

The only problem with this explanation is that causeways lead to places and connect things, while the Wall of the Crow leads to nothing at its western end but desert sand. If it was an ancient causeway, then why does it lead to nothing?

Maybe the answer is that it didn’t always lead to nothing.

In fact, the Wall of the Crow seems to lead to where Norden and de Bruijn described the location of the fourth pyramid of Giza – “it makes a series with the three others.” Could the Wall of the Crow really have been a causeway for the missing fourth pyramid?

Here, the question must be asked: if there really was a fourth pyramid on the Giza Plateau, what happened to it? Why is it, unlike the other three, not standing today? Some historians have proposed that if there was a fourth pyramid, it must have been dismantled in the 1700s and used to build the nearby city of Cairo, while others assert that its remains may still be buried beneath the desert sands.

One thing is for sure, if a fourth pyramid of Giza is concealed under the desert, it would not be the only thing hidden there …

The Lost Golden City

In late-2020, a team of archaeologists began an excavation project at an innocuous desert site near Luxor, some 300 miles south of Cairo. What they discovered under the sand shocked them.

Within weeks, a series of ancient bricks began to appear in all directions; within months, archaeologists realized they had discovered “the site of a large city in a good condition of preservation, with almost complete walls, and with rooms filled with tools of daily life.”

What they had discovered was the largest ancient city ever found in Egypt.

Longtime Egyptian Minister of Antiquities Zahi Hawass dubbed it the “lost golden city” … and with good reason. Already, extraordinary jewelry and colored pottery has been recovered from the site, but researchers believe there is much more to come. In their words, “the mission expects to uncover untouched tombs filled with treasures.”

Think about it, the largest ancient city ever found, and we didn’t even know it existed until 2020 …

Buried Structures Beneath the Sands

In fact, this is part of an ongoing theme in recent times.

In the past, archaeologists searching for ancient sites had to work off of ancient texts, hand-drawn maps, rumors, and guesswork, often searching for years without ever finding anything of note. But over the last 20 years, this all changed as satellite technology began to become more prevalent, allowing researchers to survey terrain from thousands of miles away, and investigate potential sites without digging.

In the first decade of the 21st century alone, archaeologists using satellite technology located over 3,000 ancient settlements hidden underground in Egypt, awaiting excavation and exploration. Simply, the rise of satellite imaging and so-called ‘space archaeology’ revealed a stunning truth – much of the history of ancient Egypt is still buried beneath its desert sands. That is to say, despite everything we have learned about Egypt so far, we have barely scratched the surface.

In 2008, a new era in Egyptology began when archaeologists tipped off by satellite imaging uncovered two massive pyramids buried under 25 feet of sand in Saqqara, barely 15 miles from Giza. Over the next decade, they uncovered hundreds of sarcophagi at the site which had been untouched for thousands of years, alongside an unbelievable mausoleum of mummified animals.

Consider that this discovery happened only a few miles from perhaps the greatest and most well-studied archaeological site on earth, under barely enough sand to cover a two-story house. As one researcher put it, the site at Saqqara “just shows us how easy it is to underestimate both the size and scale of past human settlements.”

So, what else might we have underestimated about ancient Egypt?

Interestingly, almost 200 years before the discovery at Saqqara, German archaeologist Karl Richard Lepsius reported the remains of a mysterious pyramid in the area. Yet nobody paid any attention to his claims, and his report was dismissed and forgotten.

But today, all across Egypt, new evidence is emerging that not only confirms forgotten or dismissed centuries-old accounts, but that seems to confirm ancient accounts believed for centuries to be little more than myth …

Unexplained Discoveries in Egypt

In the 19th century, archaeologists discovered a series of remarkable carvings on the wall of an ancient Egyptian temple. They told the story of an ancient sea voyage to a mysterious land known as Punt.

For hundreds of years, scholars insisted that the story of Punt was not meant to be taken literally, that desert peoples like the ancient Egyptians weren’t seafaring, that the story, like many ancient myths, was allegory, not historical fact.

That is, until an astonishing discovery in 2011. That year, archaeologists uncovered the remains of an ancient harbor along a desolate stretch of the Red Sea coast, including the remains of many seagoing ships. The discovery caused researchers to conclude that the ancient Egyptians “must have had considerable seagoing experience.”

More incredibly, archaeologists uncovered numerous stones and other materials engraved with extraordinary inscriptions which made specific mention of missions to a land known as Punt. In other words, archaeologists had found concrete evidence of something which to that point had been labeled myth, dismissed and written off.

One might go back further, to the work of 5th century BCE Greek historian Herodotus, who wrote of a hidden underground labyrinth which he had seen with his own eyes on his travels to Egypt.

“The baffling and intricate passages from room to room and from court to court were an endless wonder to me, as we passed from a courtyard into rooms, from rooms into galleries, from galleries into more rooms and thence into yet more courtyards. The roof of every chamber, courtyard, and gallery is, like the walls, of stone. The walls are covered with carved figures, and each court is exquisitely built of white marble and surrounded by a colonnade.”

For many centuries, the existence of a hidden Egyptian labyrinth was thought to be a myth, brushed off and dismissed by purportedly serious scholars. Until, in 2008, a study known as the Mataha Expedition used ground penetrating radar to probe the desert in Dashur, some 50 miles south of Cairo, and shockingly discovered a “huge structure hiding below the sand.”

Further exploration revealed “the presence of grid-like and ordered structures,” leading researchers to a mind-blowing conclusion. In their words: “The great lost labyrinth of ancient Egypt had been found.”

Unfortunately, the official results of the Mataha Expedition have never been released due to national security sanctions on the part of the Egyptian authorities, and all further exploration of the site has been prohibited. To this day, the site which researchers believe to be “the great lost labyrinth of ancient Egypt” has never been excavated.

Why? If something as amazing as the lost labyrinth has potentially been discovered, why would it not be investigated further? How could an archaeological site be a threat to national security … unless it contained something truly paradigm-shifting.

Could it be that what is buried underground in Dashur might force us to totally reimagine ancient Egyptian, and even human, history?

Advanced Ancient Civilization

Despite centuries of archaeological research, the unavoidable fact is that ancient Egypt remains as mysterious today as ever. The question is, what new secrets will be revealed in the coming years, what other long dismissed myths will be proven true?

What of the work of 10th century Arab historian Masoudi, who wrote of not only an Egyptian labyrinth, but the unfathomable Hall of Records which was housed there.

“Written accounts of wisdom and acquirements in the different arts and sciences were hidden deep, that they might remain as records for the benefit of those who could afterwards comprehend them.

I have seen things that one does not describe for fear of making people doubt one’s intelligence. But I have still seen them.”

Could we be primed to discover an ancient Hall of Records? And if so, what kind of secret knowledge might be recorded there?

And what of 4th century Syrian philosopher Iamblichus, who appeared to record the advanced electrical capabilities of the ancient Egyptians. Writing of his experience in the tunnels under the Great Pyramid of Giza, he explained,

“We came to a chamber. When we entered, it became automatically illuminated by light from a tube being the height of one man’s hand and thin, standing vertically in the corner. As we approached the tube, it shone brighter … the slaves were scared and ran away in the direction from which we had come! When I touched it, it went out. We made every effort to get the tube to glow again, but it would no longer provide light.”

Think about the numerous ancient Egyptian carvings and inscriptions discovered in modern times which appear to show light bulbs and other advanced technology, carvings which, like carvings depicting a sea voyage to the land of Punt, have been written off and dismissed. Might it be possible that we are about to discover hard evidence the ancient Egyptians were more technologically advanced than we ever imagined?

Already, a scientific study published in the Journal of Applied Physics in 2018 has revealed that the Great Pyramid of Giza could “concentrate electromagnetic energy in its internal chambers as well as under its base.” Will new evidence emerge in the coming years that proves once and for all the Great Pyramid was constructed to funnel electricity through its chambers and out into the world, powering an electrical ancient Egypt?

Follow this line of thinking back to the missing fourth pyramid of the Giza Plateau. Perhaps this missing pyramid is part of a much bigger puzzle.

Remember that Frederic Louis Norden described the fourth pyramid as “blacker than the common granite.” In ancient Egypt, black granite was used to symbolize regeneration, black being the color of the life-giving silt left by the Nile, and the color of the underworld where the sun regenerated each night. Black granite was often used to make sarcophagi and other important decorative artifacts and charms. So why build an entire pyramid out of it, unless that pyramid was of particular importance. What regenerative properties could the fourth pyramid have had?

And why was it purportedly topped by “a single great stone, which seems to have served as a pedestal?” What could have been on this pedestal, and could it have connected to the mysterious qualities of other Giza Plateau monuments?

Perhaps in the coming years we will find out. Perhaps it will change everything …