With great symbols representing majesty and power, mythical gods and pharaohs, and great technological inventions that changed the world, we are used to seeing Egypt and Sumer as the oldest and most advanced civilizations in history.

However, recent scientific research indicates that a mysterious ancient civilization located between Pakistan and India, predates these two incredible cultures.

Indeed, researchers believe that this civilization, known as the Harappan civilization or the Indus Valley civilization, is around 8,000 years old, which means that it’s even older than the great Sumerian civilization.

Its most famous city, Mohenjo-Daro, is a clear example of a well-established and highly advanced urban center, which includes sewage systems, roads, well-organized houses, agriculture, and artwork, among other things.

However, even with all the information that researchers already have about these ancient people, the Harappan civilization also remains one of the most mysterious in history:

Its script has not yet been deciphered, its urban planning and irrigation systems were more advanced even than most cities in modern India, and the civilization suddenly disappeared for reasons that are still not entirely clear.

How did the Harappan civilization achieve such a degree of cultural and technological development?

What was their secret?

Did someone help them, or were they the descendants of an even older advanced civilization?

And what is the mystery surrounding its sudden disappearance?

Mohenjo Daro - Heart of The Harappan Civilization

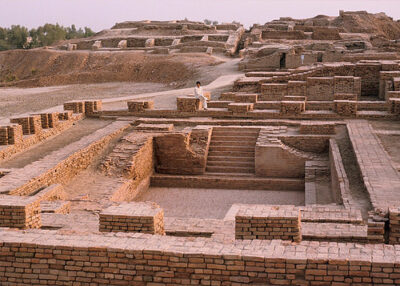

The first time a trace of this lost civilization was found was with the discovery of the lost city of Harappa in 1921. From this city came the name of the civilization we now call Harappan. Since then, more than 1,052 cities and settlements have been found. One of them, is the city of Mohenjo-Daro. This city is located near the Indus River in the Larkana district of Sindh province in present-day Pakistan and is a true gem of urban planning from the ancient era and quickly became the most famous Harappan city.

Although the ruins of Mohenjo-Daro were first found by a group of archaeologists in 1911, professional archaeological excavations were actually carried out from the 1920s to the 1930s by Sir John Marshall, the General Director of the Archaeological Survey of India.

At first, the archaeologists didn’t know what to name the city, but after their excavations uncovered many strange skeletons lying scattered in streets and houses, they ended up naming it Mohenjo-Daro, which means “the mound of the dead.”

Despite its bleak name, the city stands out as the Indian subcontinent’s first major urban center, and its sophisticated urban development is quite impressive.

The people of this city not only knew urban planning but also knew how to farm, work with metals, and express themselves in written language.

The city itself was arranged in grids, and its houses had separate rooms for different activities, including a kitchen, living room, bedrooms, patios, bathrooms, and drainage systems, much like a modern house would.

This last aspect, that of water control, is precisely one of the most impressive developments of the Indus Valley civilization.

Today, it’s easy to think that the populations that lived more than 4,000 years ago used extremely rudimentary systems to make use of water and satisfy their various needs.

For example, transporting water in buckets from the river to the houses or digging a hole in the ground to use as a toilet.

But this wasn’t the case with the Harappan civilization.

The houses had a water supply and plumbing system, with the bathrooms and toilets well separated from the rest of the rooms.

The city also had more than 700 water wells and an elaborate sewage system that allowed water to circulate harmoniously throughout the city.

Within a part of the city known as “The Citadel,” they also built a 900-square-foot structure called the “Great Bath,” which they filled by pumping water from the Indus River.

Keep in mind that the Romans only managed to build their famous baths around 70 BC, so the people of the Indus Valley were more than 2,500 years ahead.

As it turns out, this lost civilization had one of the world’s first sanitary systems.

All of this is remarkable, considering that between 20,000 and 40,000 people lived together only in Mohenjo-Daro. And Mohenjo-Daro wasn’t even the biggest city of the Harappan civilization. That would be the city of Rakhigarhi, which was discovered only in 1969, and as of today, just 5% of the site is excavated. Who knows what secrets and mysteries we may uncover about this lost civilization as the excavation progresses?

If Rakhigarhi is the largest city, could it also have served as something of a capital of the Harappan civilization? And if it did, just imagine how technologically advanced it would be compared to Mohanjo-Daro.

Mohanjo-Daro itself had very sophisticated planning, combining a water supply system, buildings, markets, granaries, and warehouses, all located in the most convenient place.

This high level of planning was impossible unless the Harappan civilization had some sort of elaborate system of weights and measurements they used for all their activities, which is still unknown to us. What we do know is that there was a strict standardization in construction, with bricks corresponding to sizes in a perfect ratio of 4:2:1.

Additionally, the people who lived in cities like Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa were true masters of farming.

Where Did The Harappan People Came From?

Because of the civilization’s age, experts continue to debate whether these people developed agriculture and animal husbandry independently or learned them from other populations of the time.

To add to the mystery, some genetic studies reveal that the farming populations of the Indus never became closely related to their closest farming neighbors, who inhabited what is now Iran and whom experts consider being the first to develop agriculture in the region, more than 10,000 years ago.

Today, it’s accepted that the spread of agriculture was carried out in different parts of the world thanks to the “export” of this knowledge that some people made.

In fact, genetic studies conducted in Europe show that stone age farmers took their knowledge to different parts of Europe as they moved through the territory and intermixed with different populations.

But this didn’t happen with the Indus Valley population since their genetics are different from neighboring people that developed agriculture before 8000 BC.

This means that the people of the Indus Valley apparently come from an earlier civilization that developed agriculture on its own or perhaps learned it from someone else.

The question then is:

Who taught the people of the Indus these advanced techniques?

Considering that the Indus Valley civilization is older than the Egyptian and Sumerian civilizations, it is also worth asking:

Were the people of the Indus Valley the ones who transmitted this knowledge to the ancient Egyptians and Sumerians?

On the other hand, the development of a complete standardized system of seals, measures, tools, and utensils served the Harappan civilization to develop international trade with populations as distant as those of the Arabian Gulf, Mesopotamia, and southern India, as evidenced by seals found in those areas.

Experts believe that most of the city’s inhabitants were merchants and craftsmen skilled in working metals such as copper, bronze, lead, and tin, as well as having great skill in working ceramics and making bricks.

In fact, they were so good that many of their creations have been found in other distant towns in the region, probably due to trade.

Religion & Government of the Harappan Civilization

Despite all this high level of planning and development, one of the aspects that have most attracted the attention of researchers is the fact that the cities in the Indus Valley lack palaces, temples, and monuments that could indicate any ceremonial practice.

There is also no evidence that there was any central authority, such as a king or queen, regulating the activity within the cities. This is something unheard of for a Bronze Age civilization, as these cultures were highly autocratic, relying on caste systems and strict hierarchies.

A good number of studies suggest that Mohenjo-Daro was a city with a community government system, with a designated group of people selected to carry out specific government tasks. Every city probably had some sort of council that, in turn, answered to a more central council that was responsible for the entire country. Considering the distance between all the various cities of the Harappan civilization, this structure of government is highly impressive. The form of government of the Harappan civilization even made the UNESCO Courier journal publish an entire article titled “The Indus Valley Civilization – Cradle of Democracy“, theorizing the possibility that democracy was invented by the Indus Valley, thousands of years before the ancient Greeks.

Another surprising thing is the lack of any huge temples for worship. If we compare it with the Egyptian and Sumerian civilizations, which were full of temples worshipping different deities, it will make the Harappan civilization extremely unique.

So far, the Great Bath seems to be the only structure in the city that could be considered a ceremonial monument.

Apparently, the people of the Indus had a particular preference for cleanliness and organization, so much so that some experts believe that it’s very likely that they had some kind of religious or esoteric practice in which the concept of cleanliness or purification was dominant.

There are even indications that these religious or ceremonial events were held in the citadel, which also reinforces the idea that these people probably worshipped water in some way.

This characteristic is very different from the culture of ancient Egypt, which is replete with temples, tombs, and other majestic monuments, as well as deep worship of their god-kings we know as pharaohs.

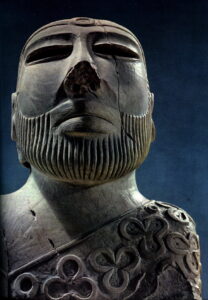

On the other hand, archaeologists have found Indo-seals and artistic figures that could be related to some religious beliefs.

A good example of this is a figurine found during early excavations at Mohenjo-Daro. This figurine is known as “The Priest King.”

However, many experts believe that this figure doesn’t represent any religious personality, as there is no solid evidence to support this belief.

Another famous handicraft found at Mohenjo-Daro is a female figure of just 4.25 inches made of bronze that has been called “Dancing Girl” for its peculiar features.

In this figure, the girl holds her left leg and hand, seemingly ready to follow the rhythm of a dance, probably of a ceremonial or religious type.

Her left arm features 25 bracelets, apparently used to help shape her limbs.

This has been a common practice in some cultures around the world throughout history, as is the case today with the Kayan, a sub-group of Karenni people, a Tibeto-Burman ethnic minority of Myanmar, in Burma.

Some experts believe that these figures and other items from the culture of the Indus people may actually represent a variety of religious beliefs and practices or a variety of gods, just as they did in ancient Egypt.

Even with all these elements, none of them represents concrete proof that the Harappan civilization had a strictly religious or esoteric practice, and this is only speculation and theory.

The Indecipherable Script of the Harappan Civilization

In the end, there is something on which most experts agree: much of the mystery behind the Harappan civilization can only be unraveled when the greatest of its mysteries is solved – its script.

Although experts have already managed to decipher much of the culture’s way of life and their city-building methods, most of its mysteries remain hidden behind the veil of its script.

Unlike what has happened with Egyptian hieroglyphics or the Mayan language, the Harappan script is reluctant to be deciphered.

The mystery behind the undecipherable Harappan script baffled scientists for so long that since 2004 there has been a $10,000 cash prize for anyone who can decipher a Harappan text of around 50 characters. Not surprisingly, no one has managed to do that.

With this culture wrapped in so much mystery, decyphering its script could be the only key that would allow us to unlock its secrets.

Today, hundreds of symbols belonging to the Harappan people have been found on a large number of craft objects of all kinds, including ceramic and metal handcrafts.

The majority of these symbols depict animal and human figures.

However, many experts believe that these symbols don’t really represent a writing system, but rather deities, sects, clans, and family names.

Others believe that the symbols represent a series of seals used for commercial transactions.

This is similar to the symbols we can find on modern coins and stamps, which in many cases, stand for certain types of encoded information.

Another aspect that works against the Harappan script as a form of written language is that most of the inscriptions usually have only 4 or 5 symbols drawn on small surfaces about an inch long, and the longest known Harappan script doesn’t reach 30 characters.

This is very different from what can normally be seen in the writing systems of other ancient civilizations, which often have more than 100 characters.

Nonetheless, some studies comparing the Harappan script to other systems of symbols, both linguistic and non-linguistic, discovered that the Harappan script closely resembles a written language in a high percentage of cases.

This similarity applies not only to writing systems based on disordered codes like DNA but also to ordered code systems like computer programming languages.

However, there are still many doubts about the Harappan script due to the great difficulties it continues to present, even to be decoded by statistical systems run by powerful computers.

One of the main problems with this script is that the messages are too short and show few examples within each sequence, which makes things difficult even for machines.

On the other hand, the symbols that appear next to images vary in each stamp, thus lacking homogeneity and clarity, which further complicates a standard interpretation of this writing.

This means that up to this point, any interpretation made can be considered more conjecture than fact.

Another factor that also plays against the decoding of the Indus Valley texts is the absence of any multilingual inscription, that is, a text written in two or more known and unknown languages that say exactly the same thing.

The best example of this is the famous Rosetta Stone, the ancient inscription that has text written in two forms of Egyptian script and one in ancient Greek script, which greatly helped to decipher the language of ancient Egypt.

Despite all the obstacles and problems against it, the work to try to decipher the Harappan script continues.

Hopefully, one day we’ll be able to decipher the script and discover the secrets this civilization hides.

The End of the Harappan Civilization

What we know is that the Indus Valley Civilization ended around 1700 BCE. But what happened exactly is still a mystery. Were their cities abandoned? Or were they attacked by hordes of invaders from other regions? Or perhaps something else happened, which we still can’t understand?

Oddly enough, these questions still remain unanswered as experts have yet to find hard evidence.

To date, most scientists are basically divided into two groups:

Those who believe that the cities were abandoned due to a great flood or drought of the Indus River or the Ghaggar-Hakra river, and those who believe that its inhabitants were massacred by invaders.

Precisely, this last theory is the one that contributed to giving the name to the city of Mohenjo-Daro. As we already mentioned at the beginning of the article, Mohenjo-Daro means “the mound of the dead.”

This refers to a number of human skeletons found in the city’s ruins when excavations began in the 1920s.

However, aside from broken statues and structures, only these human skeletons, which were around 40, were found.

What happened to the rest of the 40,000 inhabitants that the city was supposed to have?

Some experts consider that it’s necessary to discard the theories about the end of the Harappan civilization at the hands of armed invaders, since there are several elements that don’t fit in this story.

First, there is no major evidence that a full-scale invasion occurred. For example, there are no signs of burned fortresses, no destructions on the walls, no remains of weapons or armor, and no large number of skeletons of civilians and soldiers scattered everywhere.

This is quite mysterious considering that, according to the massacre theory, the invaders were the ancient Aryans, a people who settled during prehistoric times in what is now Iran and the northern Indian subcontinent.

If there was a big battle, where are the skeletons of the fallen combatants and civilians?

It is as if the earth had suddenly swallowed them…

However, the theory of the massacre still remains in the minds of many.

When the first excavations began at Mohenjo-Daro, the first thing that impressed the researchers was to discover that these skeletons were found in strange positions.

A certain number of skeletons were found in the Lower Town area, a kind of residential district, in what would appear to be some kind of unconventional burial ritual.

But another group of skeletons was found with a strange attitude.

Specifically, as if they wanted to escape from something or someone…

It’s as if death had come from inside the city and not from outside…

On the other hand, the Vedic texts could give some clues about what really happened in Mohenjo-Daro.

Some Vedic hymns indicate that Indra, the main god of these texts, attacked the fortresses of the Dasyu by setting them on fire.

In this context, a Dasyu represents any non-Aryan enemy, such as the people of the Indus Valley…

Although there are many strange theories, including a theory that suggests that some sort of advanced weapon was used to destroy the inhabitants of the cities, some researchers point out that the end of the Indus Valley civilization most likely came by more natural means…

Some experts believe that a flood or a severe drought could have been the causes that forced the people of the Indus to migrate to other territories.

However, researchers also point out that this natural disaster continued over time and that the inhabitants endured as much as they could, even changing a large part of their diet, as evidenced by the remains of food found in the area.

Are There Other Advanced Civilizations Lost in History?

One of the most technologically advanced civilizations of the Bronze Age, the Harappan civilization continues to be shrouded in mystery, and its discovery only led to more questions than answers.

Although there is still much to discover, the most important thing is that we now know that this ancient civilization left an important historical and cultural legacy.

And if such an important civilization was lying underground for thousands of years and we only discovered it 100 years ago, just imagine what other secrets and mysteries still remain hidden beneath the ground.

What other chapters of the development of human civilization remain undiscovered? And how advanced ancient humans really were?